*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

A recent study posted to medRxiv* preprint server revealed that gut microbiome predicts atopic outcomes in infants with decreased bacterial exposure.

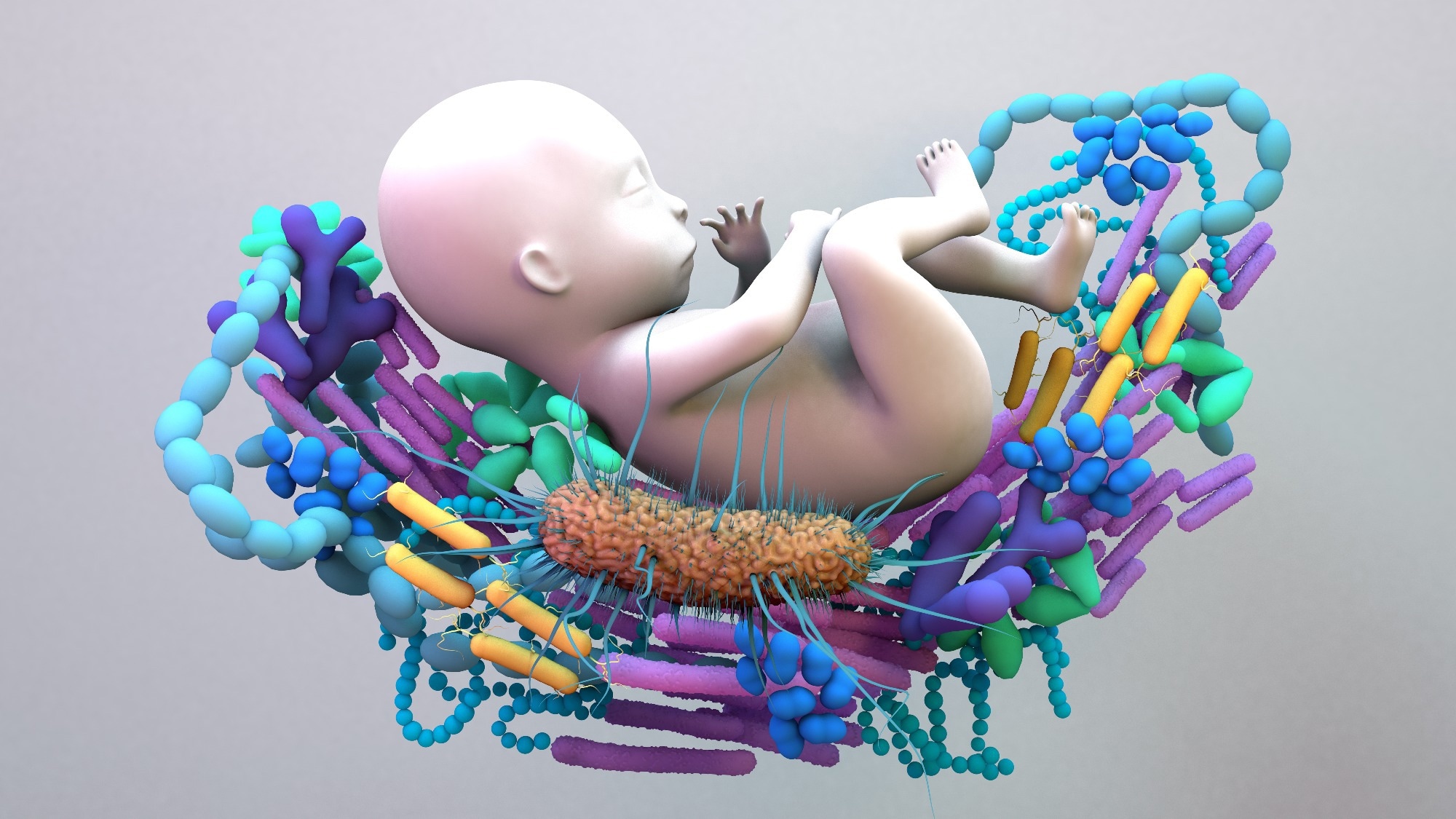

Study: Gut microbiome predicts atopic diseases in an infant cohort with reduced bacterial exposure due to social distancing. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock

Study: Gut microbiome predicts atopic diseases in an infant cohort with reduced bacterial exposure due to social distancing. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock

Background

Body cavities and mucosal surfaces in humans harbor diverse microbial communities, which regulate host metabolism, immunity, and epithelial barrier function. Changes in microbial transmission through industrialization- and western diet-associated lifestyle factors may lead to the rise in non-communicable diseases in affluent societies.

The study and its findings

In the present study, researchers evaluated interactions of microbial exposure and fecal microbiome composition with atopic outcomes in the cohort of infants born/raised during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related social distancing (CORAL). In this cohort, most infants were males (55%), Caucasian (96%), and born by vaginal delivery (65%).

The team performed 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing on fecal samples from infants. They observed a strong association of microbiota composition with birth mode and age. Age was associated with 33% of the detected bacterial families.

At the order level, Veillonellales, Enterobacteriales, Lactobacillales, and Bifidobacteriales decreased from six months to one year, while Bacteroidales, Erysipelotrichales, Coriobacteriales, Verrucomicrobiales, and Clostridiales increased.

Cesarean-section (CS) delivery or intrapartum antibiotic exposure during vaginal delivery was associated with a higher relative abundance of Flavonifractor, Erysipelatoclostridium, and Sarcina and a lower relative abundance of Collinsella at six months. CS delivery was also associated with a higher abundance of Blautia, Amedibacterium, Roseburia, and Enterobacter and a reduced abundance of Parabacteroides and Bacteroides.

Most birth-mode differences were not significant by 12 months of age. Next, the team compared microbial composition between CORAL and historical cohorts. The time-dependent abundance of Bacteroidia, Proteobacteria, and Bacilli was similar between CORAL and historical cohorts, although Clostridia were significantly lower in CORAL infants at six months and one year.

Compared to a pre-pandemic Irish infant cohort, Clostridia levels were lower at six and 12 months, but Bifidobacteria were more abundant at one year in CORAL infants. CORAL infants also had higher microbial richness at six months. Diet was identified as the principal determinant of gut microbiota composition at six months and one year.

The effects of CS delivery, intrapartum antibiotics, and medical interventions were higher at six months, while the impact of environmental factors and exposure to human contacts increased at one year. In addition, the intake frequency of beans, grains, sesame seeds, and vegetable oil was significantly associated with microbiota composition at six months.

Additionally, walnuts, soy, cow’s milk, and pecan ingestion significantly contributed at 12 months. The effect of beans, nuts, and oil was similar to that of vaginal delivery and breastfeeding, with higher relative abundances of Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, Bacteroides, and Lactobacillus at either time point. However, consuming cow’s milk formula had the reverse effect at 12 months, with the microbiota composition shifting away from the Bacteroides/Bifidobacterium-dominated one.

The impact of human exposure-linked factors increased by one year, shifting the infant-type microbial composition to a more mature one with higher abundances of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae.

Since environmental factors (diet, breastfeeding, etc.) have been described as epidemiologic factors influencing food allergen sensitization and atopic dermatitis, the authors next investigated how much the microbiota mediated the effects of epidemiologic factors.

To this end, they compared the impact of exposure on disease outcomes using logistic regression models. Gut microbiota composition at both time points significantly predicted atopic dermatitis at 12 months. Atopic dermatitis showed a positive association with smoking and attending daycare. It had a negative association with living in rural areas and antibiotic use from six to 12 months of life.

The microbiota mediated the effects of antibiotics and daycare, whereas smoking was primarily a direct effect. Atopic dermatitis was also positively associated with the infant intake of fish, pistachios, starchy vegetables, and peanuts and negatively with the intake of kimchi, grain, and pine nuts. Several food items had direct and microbiota-mediated effects.

Gut microbiota composition at six months strongly predicted food allergen sensitization at 12 months. CS birth or having siblings was associated with a reduced abundance of microbes associated with food sensitization. Egg showed a direct negative association with food sensitization, while tempeh had a direct positive association.

Conclusions

In summary, the researchers demonstrated that COVID-19-related social isolation measures altered infants’ early life gut microbiota assembly, which was linked to the risk of atopic diseases.

Furthermore, they established that the microbiome partly mediates the epidemiologic associations between the risk of atopy and antibiotics, diet, and breastfeeding. Whether these differences are short- or long-lived needs further investigation.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.