The embryonic and fetal periods of life are vulnerable to impact by harmful chemicals in the environment. These include microplastics (MPs), which have been found in many living organisms and tissues, stemming from the environmental degradation of waste plastics. Using placental tissue and meconium samples, a new study examines the links between exposure to MPs in pregnancy and microbiomes.

Study: The Association Between Microplastics and Microbiota in Placentas and Meconium: The First Evidence in Humans. Image Credit: SIVStockStudio / Shutterstock

Introduction

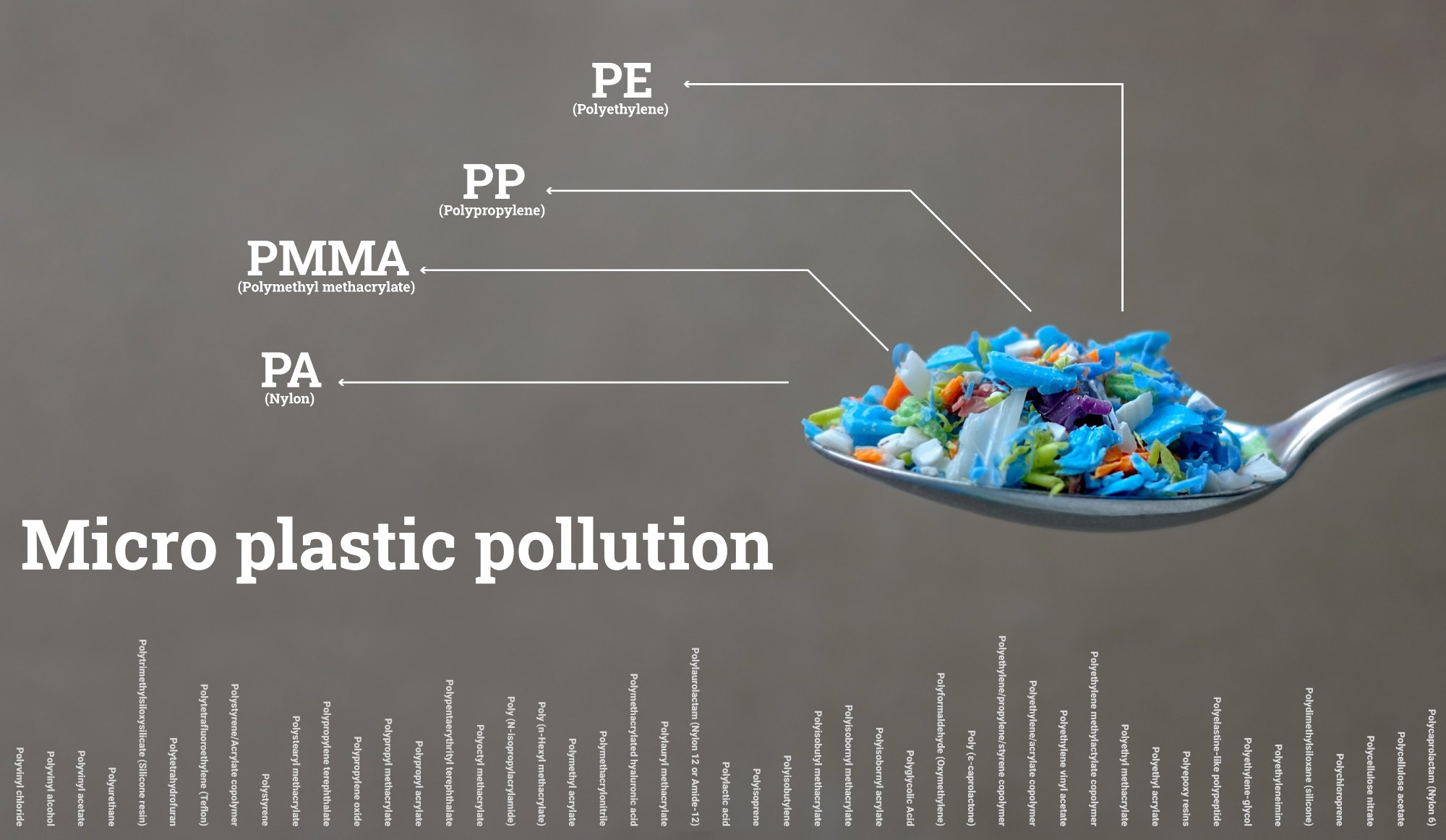

MPs are plastic particles with a diameter of 5 millimeters (mm) or less. Most MPs are formed by the degradation of plastics by ultraviolet radiation, biological means, heat, oxidation, or light exposure or are intentionally formed as microbeads to be incorporated into personal care products.

MPs exist throughout the ecosystem, whether on land, in the air, in the water, or in the food chain. Several earlier studies have demonstrated their ingestion and inhalation by humans, potentially posing a significant health risk.

The current study, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, attempted to identify them in placental and meconium samples. Prior research has shown potentially higher exposure to MPs among infants than adults, a matter of concern since polystyrene nanoparticles have been shown to cross the placental barrier to enter the fetal tissues from the maternal lungs in mammals, as well as in placental tissue.

Animal experiments showed the ability of ingested MPs to disrupt the normal intestinal epithelial barrier and affect the gut microbiome. There is, however, a lack of human evidence on the potential for placental microbiota changes to affect the metabolism of the mother-fetus unit, cause gestational diabetes mellitus, or increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as low birth weight or preterm birth.

The fetal and early neonatal microbiome depends on the maternal microbiome in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and vagina. This Chinese study was carried out in 18 mother-infant dyads in order to detect any association between placental and fetal MPs. Samples were taken during pregnancy and examined for MPs’ presence using a laser infrared imaging spectrometer (LDIR). Correspondingly, microbiota were assessed using 16S rRNA sequencing.

What did the study show?

The mothers in the study had a median age of 32.5 years with normal body weight. Only MPs sized 20-500 μm were counted to maintain accuracy within LDIR limits.

The researchers found traces of MPs in all samples, mainly polyurethane (PU) and polyamide (PA). More than three-quarters of the MPs were between 20 and 50 μm in size. The median concentration of MPs in the placenta was 18 particles per gram, vs. 54 particles/g in meconium.

The presence of polypropylene (PP) in the placenta showed a positive correlation with the total MPs and with PA and polyethylene (PE) in the meconium. Placental polyvinyl chloride (PVC) also showed a positive association with meconium PA.

The microbiome in placental and meconium samples showed a predominance of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Firmicutes. In placental tissue, these made up over 40%, a third, and a fifth of the total, vs. a third each for the first and the third, and 28% for Bacteroidota in meconium samples. However, beta-diversity and composition differed significantly between the two types of samples.

Several genera of bacteria were reduced with increasing polyethylene (PE) concentrations. Overall, multiple genera showed abundant changes in association with total MPs and with PA and PU.

In placental samples, for example, increasing total MPs and PA concentrations were positively correlated with the abundance of Porphyromonas. PE increase was associated with a decrease in multiple genera, including Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcus. With higher levels of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or PVC, there was an increase or decline, respectively, in the concentration of Escherichia coli.

Meconium samples showed a positive association between total MPs and some genera like Streptococcus and Clostridia. In addition, specific associations were also identified, such as a positive correlation between Treponema and PA and a negative one with PU.

Again, particle size showed varying correlations with the abundance of several genera in the placental microbiota, such as Sediminibacterium with MPs between 100 and 150 μm, vs. certain Lachnospiraceae with MPs over 150 μm, in the placenta. With meconium, too, several positive associations were identified between specific genera and MPs sized 50−100 μm

What are the conclusions?

Earlier studies indicate that the predominant MPs differ between regions and in different studies. This could be due to differences in experimental methods.

PA and PU dominated exposure in this study. Both plastics are used widely in multiple product areas because of their performance and resistance characteristics. Household dust and indoor air may thus have high levels of these MPs, representing a high exposure risk for pregnant women and infants.

Other sources like groundwater and reservoir water show mainly PA, PE, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET), but PU was found in raw water and drinking water treated conventionally.

The current study shows PA, PU, PE, and PET to be the most abundant in placenta and meconium, with positive correlations between certain MPs and total MPs. Moreover, placental PVC showed a positive association with meconium PA. However, these patterns may be due to similar or identical intake sources.

The increased meconium levels of total MPs and PA in meconium compared to placental samples could indicate that the fetus is exposed to these plastics by other routes as well, though the accumulation of these particles throughout gestation may be a more straightforward explanation.

“MPs could have an important antibacterial effect on key members of the placenta microbiota and meconium microbiota.” This is reflected in the consistent effect of total MPs, PA, and PU on multiple meconium microbiota genera.

Not only are MPs found widely in both placental and meconium specimens, but their concentrations may affect the microbiomes in both the fetal gut and placenta.

This is “the first study to pay attention to the possible effects of MPs exposure for human microbiota.”

The extensive levels of exposure indicated by this study of pregnant women and fetal meconium are concerning. In addition, the particle size is related to the changes in the fetal meconium microbiome, with a size between 100 and 500 μm showing robust associations with such effects.